Leaders in a school health center setting may not fit the typical image of a school leader. Some of our most successful ‘leaders’ were recommended by their school health center staff simply because they were active users of the school-based health center (SBHC)… once they joined the Youth Advisory Council they took on more leadership, since they felt ownership of their SBHC.

Youth leadership supports youth in “developing the ability to analyze their own strengths and weaknesses, set personal and professional goals, and have the self-esteem, confidence, motivation, and abilities to carry them out.”1 Through leadership development, health centers can mentor, guide, and train youth to become dynamic advocates, managers, and participants in health center projects. Providing leadership training prepares youth to manage time, work in a team setting, set goals, start conversations, facilitate meetings, and make effective presentations; all of which are positive life skills that they will carry into adulthood.2

Youth leaders who can motivate their peers and lead by example will make the youth group stronger and more effective. However, these leaders will not come out of the woodwork. Young people become effective leaders when services (the provision of resources, knowledge, and goods to/for youth) and supports (like interpersonal relationships) are in place to foster opportunities (the activities, roles, and responsibilities done by youth).3

Think of every young person as someone who possesses leadership potential. Not everyone feels comfortable leading a meeting or speaking at an event, but they may be able to talk to teachers about a project or draft a letter to the school or community newspaper. It’s worthwhile to think about all of the ways youth can get involved in the health center.

It can be difficult to find time to meet with youth individually, but it is crucial. Plan to meet regularly with core leaders and be on the lookout for impromptu individual meetings. These could happen while walking with a youth to get a snack before or after a meeting.

Sometimes it’s hard to take a step back and play the supportive role, but it is the only way to develop leaders authentically. You can have a negative impact if you ask a youth to take ownership of a task and then decide to do it yourself. When leaders do not come through on an assignment, it’s important to hold them accountable. At the same time, you must examine the skills and assistance you provide to the group to ensure that expectations were clear, a timeline was created, and follow up took place to inquire about any extra support needed. Make sure young people have the guidance needed to complete agreed upon activities.

Youth need training to understand public health issues, education models, and methods of effective publicity. Trainings can be facilitated with in-house staff or in collaboration with an outside resource person, so youth feel confident in their knowledge and skills. This is as true for making posters as it is for leading a meeting or talking to school administrators. As tasks get more advanced, the level of training should progress as well. Ensuring youth are ready for each task will boost their confidence and make effective use of their time.

One of the first things a young person can do is help promote the health center. He or she can connect with their peers in ways that the health center staff cannot fully replicate. Having youth ambassadors will not only bring more youth to the center, but also help keep providers and staff abreast of the needs of the population served. Here are a few steps to get outreach going:

Projects Youth Can Undertake to Promote a Health Center

Youth Advisory Councils (YAC) are useful way for adult staff to receive feedback and recommendations in order to ensure youth-friendliness of health center operations. “The basic purpose of a YAC is to give youth a voice within a program or organization. Having a thorough understanding of where exactly the YAC fits within the organizational structure can influence the mission, goals, and direction that the YAC will take.”4 Because of their far reach on the school campus and involvement in community activities, YAC members are able to inform adults of popular perceptions of the center and how to respond to the needs and requests of potential patients.

YACs can also serve as a pipeline for youth interested in learning about educational and career opportunities in public health. Consider bringing health professionals, including individuals from the health center’s sponsoring organization, to share about their public health career. Additionally, some health centers and sponsoring agencies invite YAC members to sit on the board of directors as school health liaisons and voting members, building their understanding of organizational governance. Try to make every aspect of the YAC a skills-building one: group facilitation and consensus building, meeting organization, agenda development, event planning, and networking should be practiced thoroughly.

Incorporating youth engagement into the community assessments and research involved in opening a new health center or evaluating current services can build youth leadership skills. This can be a concrete introductory project for youth and would benefit a new health center. Youth can design a needs assessment tool to assist the health center with planning for operations. Young people can participate in every stage of the research process; from administering the survey and collecting the data to analyzing the findings, developing recommendations, and disseminating results to various audiences. All of this can be done in collaboration with adults providing training and guidance along the way.

Peer-to-peer education is the teaching or sharing of health information, values, and behavior in educating others who may share similar social backgrounds or life experiences.5 In this model, young people focus on a particular health issue in their school or community and set out to teach their peers about it. Groups may focus on teen pregnancy, healthy eating, asthma, or teen dating violence. The key component is to allow the youth to choose a topic that is important to them and is a need for the larger school population.

Peer-to-peer education can take place on a large scale, such as an assembly or video, or it can be focused on small groups or individual persons. For example, youth can make class presentations, run small discussion groups, or mentor younger youth.

In many ways, using the peer-to-peer education model is much like starting an outreach group to promote the health center:

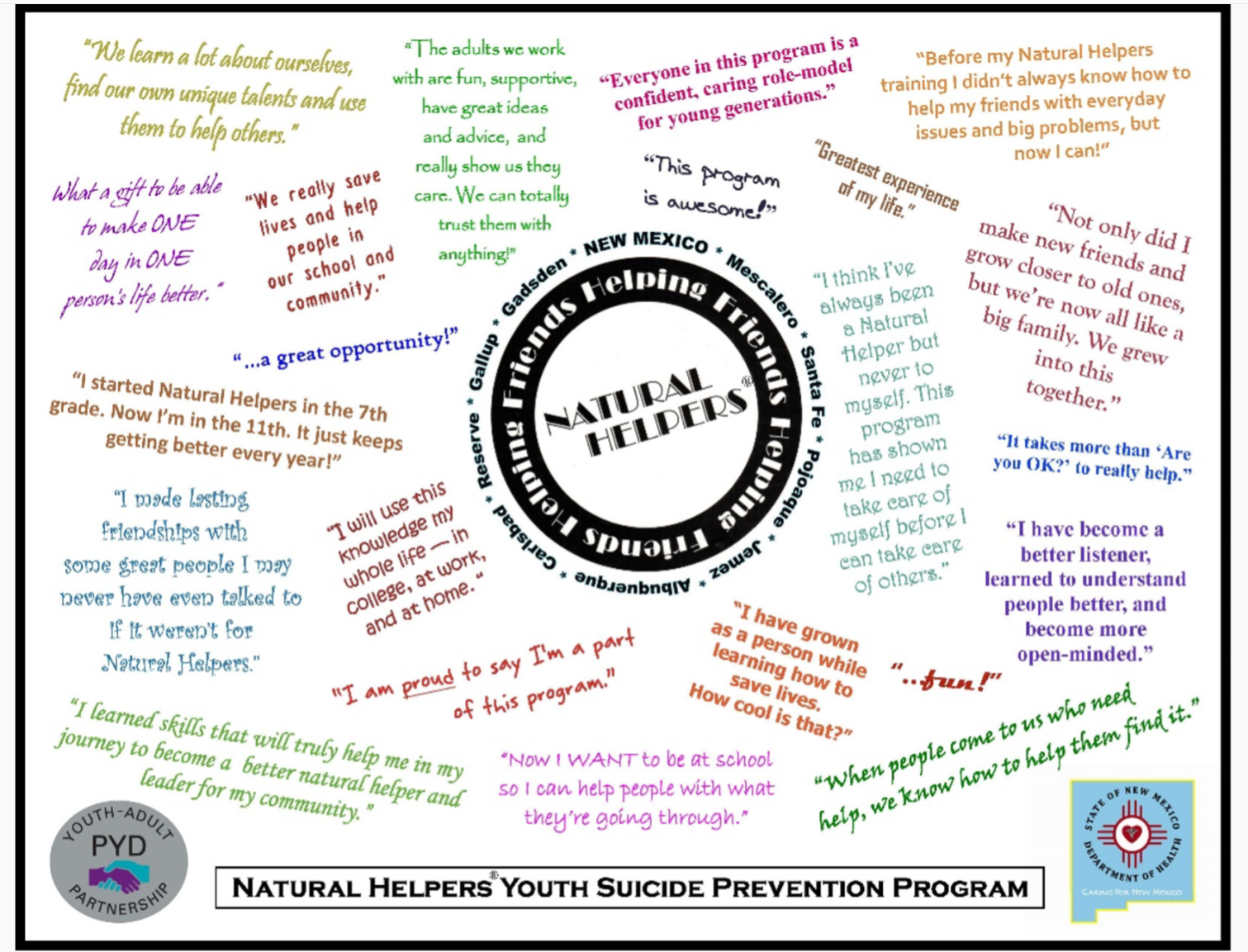

Natural Helpers is a statewide peer-to-peer education program that has seen over 20 years of success in responding to the needs of New Mexico youth. Peer-to-peer education, or the teaching and sharing of health information, values, and behavior in educating others who may share similar social backgrounds or life experiences, allows youth to confide in people they already trust, their friends. The program first began, in 1994, in response to concerns from school leaders over teenage suicide and other problems. The program aimed to open lines of communication among peers and create a safe and supportive school and community environment.

By training Natural Helpers in listening skills, problem solving, awareness of resources, and exercising self-care, students could provide support to both their peers as well as adults. The response to the program was overwhelming positive; students felt more comfortable coming to friends, and staff and parents felt comfortable knowing Natural Helpers were knowledgeable of health center services and trained to be aware of their own limitations. Today, there are 20 Natural Helpers programs across New Mexico that have trained thousands of students to be leaders and advocates in their community.

Natural Helpers credits much of its success to the adaptive recruitment and retention strategies the program employs. Firstly, Natural Helpers are not chosen based on any academics. “Typically, an anonymous school-wide survey identifies the young people that others [already] seek out for help.” The survey also identifies a few adults within the school that are invited to be official “sponsors” of the program. The selected group then attends a 25-hour retreat, away from school in a camp setting, where they participate in outdoor experiences that foster team-building, trust and resiliency. Inevitably, bonds form among the group members, creating a cohesive and supportive dynamic among what was a collection of very diverse individuals who thought they had little in common with one another just days before.” Training continues throughout the year and bonds are maintained through weekly meetings where members offer support to one another.

Through leadership development programs like Natural Helpers, support networks are established that motivate youth to fully participate in community life. Most importantly, youth obtain knowledge and skills that instill the confidence to effect positive social change in their schools and at home.